Women, gender, and mobility

16.06.2021

The subject of women and mobility has been widely discussed in media, at events, and in politics since 2019. Again and again the core message of these debates has been: “Women’s mobility is different to men’s. They have other needs and requirements”. But what does that mean exactly? How can these differences in be explained and what are the implications for the mobility transition?

Women’s mobility

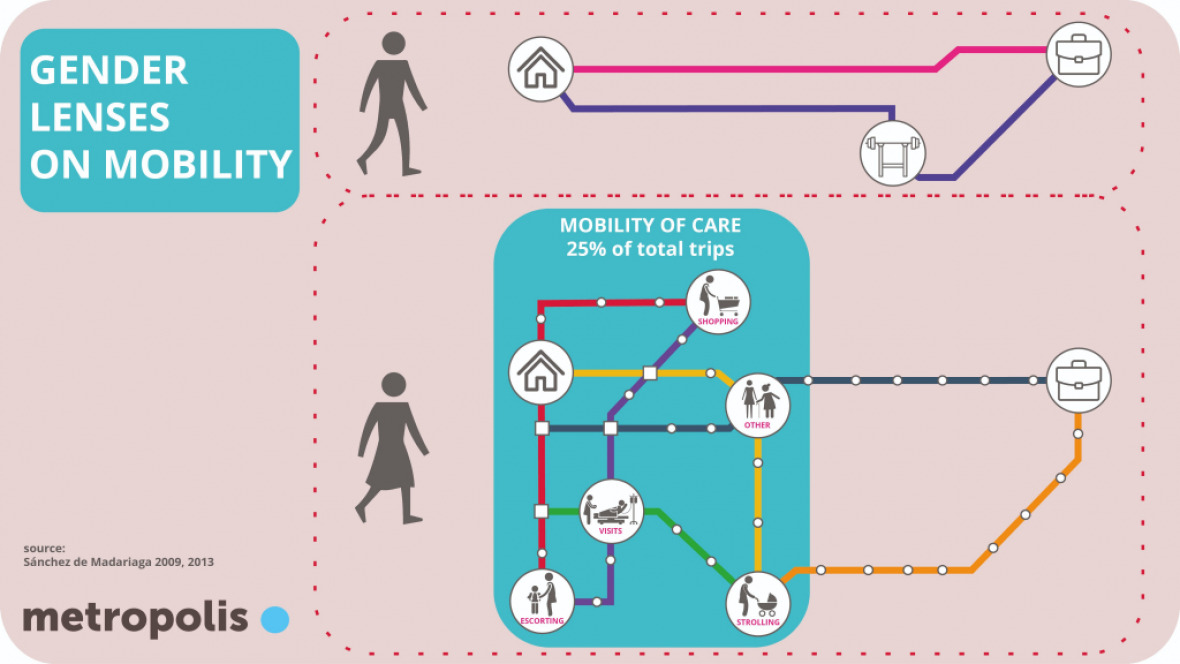

Transport statistics reveal significant gender differences in mobility behaviour (see for example studies by Best and Lanzendorf, Kawgan-Kagan and Popp, Nobis and Lenz). Gender, in combination with other socio-demographic variables such as income, age and household composition, can explain differences in the duration, frequency, type and purpose of journeys. For example, women make more trips per day compared to men, but the distance traveled each time tends to be shorter. Women also drive less, walk more, cycle more and make more use of public transportation services.

This is primarily because most of the journeys made by women are for the purpose of undertaking routine errands or accompanying people with limited mobility (children and elderly people, people with assistance needs). Female mobility behaviour is thus more diverse, more social and less linear.

These mobility patterns reveal something more: Women‘s specific mobility behaviour is not biologically determined, rather it results from social roles and the gender-specific division of labour. This is why we speak of gender-specific mobility behaviour, referencing the distinction between biological sex and socially constructed gender.

Gender specific mobility needs

Gender and the associated expectations and division of labour result in specific demands on transport infrastructure and means of transport. Examples of gender-specific mobility needs are safe and barrier-free infrastructures. These include, among other things, protected bike lanes, wide sidewalks, ramps, elevators, and wider doorways. Not only do these measures enhance the comfort of people with reduced mobility, they also improve the safety of the most vulnerable road users.

As women today are confronted with the demands of both reproductive and productive work, the ability to flexibly combine different modes of transport is particularly important. This double burden translates into both a greater need for mobility and greater time pressure in mobility. These mobility requirements also apply to men involved in care work. In addition, significantly lower incomes and women's specific physical experiences and the associated fears, such as of being assaulted in public spaces, also result in further demands on mobility and the design of public space.

Unfortunately, these gender-specific mobility needs are not adequately taken into account in the planning of transport infrastructure and the design of new mobility services such as car-sharing, ride-pooling or e-scooter rental services. Many new sharing services, for example, do not meet the actual everyday needs of women. As a consequence, women use these offers less.

This raises the obvious question: Why are these diverse mobility needs not considered in planning and design?

Is automobility the problem?!

The focus of urban infrastructure on cars since the 1950s does not reflect – and indeed runs contrary to – the (mobility) needs of many other road users. Although urban road networks, which are planned and constructed in a star shape, offer automobile users fast and easy access from residential suburbs to workplaces in the city centre, they are only designed for the ease of a small group of mostly male commuters.

This, coupled with the automotive sector’s focus on building vehicles that are "ever faster, bigger and more efficient", has meant that cars are closely linked to a traditional ideal of masculinity. The car has long been a symbol of male dominance or, in the words of Judith Butler, a "male practice" that is pursued at the expense of other road users. Men are significantly more likely to be the cause of serious and fatal accidents. This is especially true for often trivialized risk behaviours such as drunk driving, speeding or parking tickets.

This male dominance of the transport sector through automobility and the concurrent neglect of other mobility needs is reinforced by gender gaps in the mobility sector. Just 34 % of all management roles at the Federal Ministry of Transport and Digital Infrastructure are filled by women; in urban planning women occupy 33 % of all management roles; and women account for just 5.6 % of the seats on the executive boards of the 50 largest transport companies. Germany has never had a female federal transport minister.

Even the shift from combustion engines to electric- or hydrogen-powered vehicles is having little effect on the low level of gender sensitivity in the transport sector and its transformation. The new drive technologies even contribute to the perpetuation of male structures and the associated socio-ecological consequences. Is the mobility transition being driven by men for men?

Where to from here?

Firstly, an examination of gender aspects in mobility allows us to broaden the debate beyond "women's issues". Studying female mobility can help to identify structures and develop solutions that are not only beneficial to women, but to all people with mobility needs other than simply commuting to work by car. But it's not quite that simple. Gender is not the only criterion that shapes our behaviour and our lived realities and, as a consequence, our mobility behaviour and needs. Other social power relations, such as racist and capitalist structures, also play a role. Consequently, the sole cause cannot be found in automobility.

But in order to make further progress in the mobility transition that so many desire, individual privileges, especially male privileges, which are entrenched in automobility (among other things) must be broken down. The mobility transition is about more than ecological solutions; we must also take into account the different opportunities and needs of women and marginalised groups. Inclusivity and mutual respect must play a greater role. What we need is a paradigm shift. After all, mobility is crucial to participation in public life, it is an essential public good and thus a core element of a democratic, stable and just society. It must be the aspiration of policymakers in general, but also of urban and transport planning authorities, to facilitate the participation of all people by representing all social groups and genders and taking into account other types of discrimination such as ethnicity and class.

This blog post was first published on 15 June 2021 on the EXPERI website.